Please consult our COVID-19 policies and resources for guidance on attending public performances.

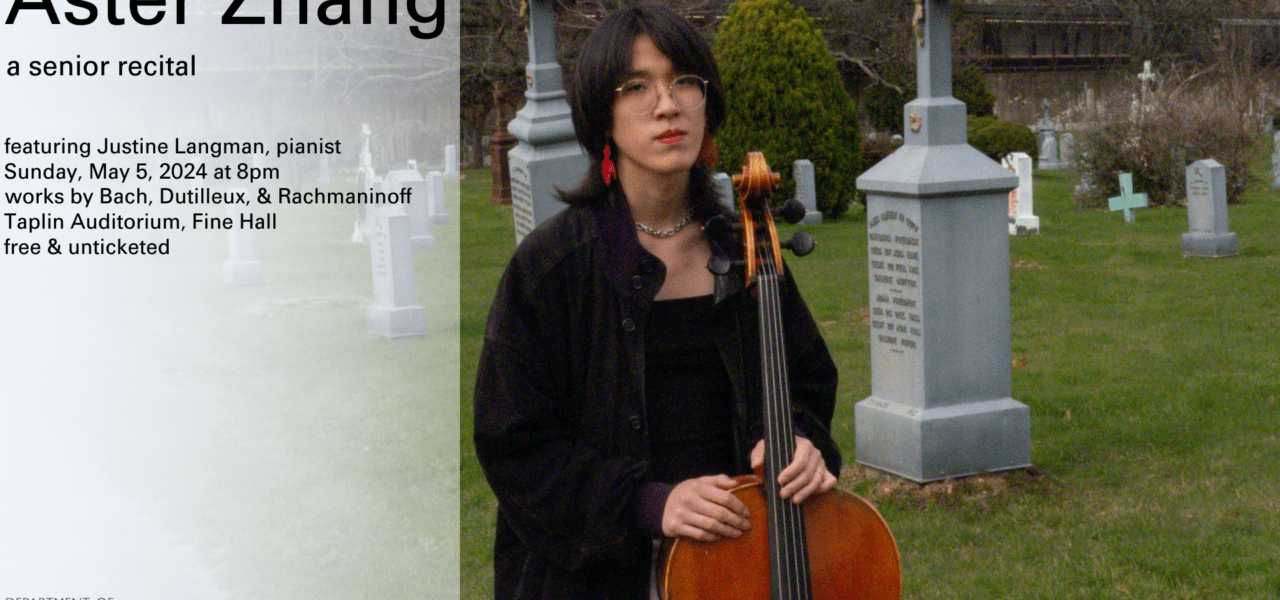

Certificate Recital: Aster Zhang, Cello

Presented by Princeton University Music Department

date & time

Sun, May 5, 2024

8:00 pm - 9:00 pm

ticketing

Free, unticketed

- This event has passed.

Aster Zhang ’24 (Cello) performs a senior recital.

Program

J.S. BACH Suite No. 5 in C minor

I. Prelude

Duration: 7 minutes

HENRI DUTILLEUX 3 Strophes sur le nom de Sacher

I. Un poco indeciso

II. Andante sostenuto

III. Vivace

Duration: 11 minutes

SERGEI RACHMANINOFF Sonata in G minor for Cello and Piano

Justine Langman, piano

I. Lento - Allegro moderato

II. Allegro scherzando

III. Andante

IV. Allegro mosso

Duration: 40 minutes

Program Notes

J.S. Bach’s Suite No. 5 for Cello in C minor, the penultimate entry of his six revered dance suites for unaccompanied cello, is enigmatic: at once the culmination of the strikingly polyphonic melodic lines he had developed in his cello writing and also a complete musical departure of expression. Set in the intense, mournful key of C minor, and originally written in scordatura with the A string tuned a whole step down, the suite is permeated throughout with a lamenting air, suffused with warm and dark colors. Bach moves with seamless grace from burning anger to spirited dancing, and then overwhelming desolation.

The Prelude to the fifth Suite is unique among Bach’s six preludes for the cello in that it is bifurcated very clearly into two sections: a drawn-out, slow introduction in the style of a French overture and a fast-paced dance in triple meter. The former is rife with melisma, cascading up and down the cello’s lower ranges; it distinguishes itself from the other preludes in Bach’s oeuvre, many of them fast-paced and relentlessly modulatory, in its willingness to dwell in the key of C minor at a tempo reminiscent of a funeral dirge. Towards the end of the first section, the cello has an extended melismatic passage which completes the modulation in the “overture” into G minor, a brighter key that better-serves the dance to follow.

The second section is written entirely as a fugue in the form of a dance. The cello handles both the melodic line and its counterpoint in turn, rapidly alternating between the two. Readily apparent in the fugue is the use of sequential phrases, where a phrase of interest is repeated in a “sequence” of different keys, often in order to build anticipation for a dramatic re-statement of the subject. Perhaps most remarkable, an outlier among his cello work, is Bach’s usage of an adjacent open string, often the dominant tone in the key being played, to build volume, intensity, and tension.

The dance gradually grows in fervor and intensity before abruptly derailing; finding its footing once again, the line reaches a fever pitch with punctuated chords before ending on an incandescent, strikingly joyful Picardy third. PROGRAM NOTES By Aster Zhang ’24 The 20th-century cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was the sole primary force shaping much of how his contemporary composers and musicians approached the cello as an instrument. His famous virtuosity and uncompromising approach to musical interpretation influenced a generation of cellists, as well as a generation of composers.

The 3 Strophes sur le nom de Sacher, composed in 1976, exemplify Rostropovich’s influence at a remarkably large scale. They represent Henri Dutilleux’s contribution to a cycle of 12 pieces for unaccompanied cello in commemoration of the 70th birthday of conductor Paul Sacher. All twelve of the pieces in this cohort have the feature of drawing their theme from the note names corresponding to the letters in “Sacher”: E-flat, A, C, B, E, D.

Sacher develops this theme over the course of three “stanzas”. The first seems to meander across different manifestations and statements of the theme. It begins with a jolting, wary stutter: an E-flat, which dies down; then an E-flat followed by an A, which fades faster than it entered. Abruptly, the name in its full spelling spills out with astonishing rapidity, as if said in a hurry, a panic. Dutilleux sweeps in this movement from left to right in the letters of Sacher’s name, then from right to left; then, skipping back and forth with haphazard, reckless steps. The movement quotes from Bela Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, a notable work commissioned by Sacher, and then fades away.

The second stanza has the air of a nocturne, evoking in its sparse but deft use of the cello in its entirety works by Dutilleux’s contemporary Hans Werner Henze. Left-hand pizzicato, polyphonic with long bowed phrases which evoke hints of tonality, drive carried-over notes and Dutilleux explores the stratospheric ranges of the cello with rarely-played harmonics on the G and C strings. The transition to the third stanza is abrupt, following a held-out A harmonic marked “longa”. The cello launches into the last third of the piece with rapid restatements of Sacher’s melody at a whispering dynamic. At the climactic moment of the piece, the cello screams Sacher’s name at its highest possible dynamic and register unendingly, faster and faster, before choking on silence. After regaining its senses, the cello races toward the end at a breakneck pace, ending dramatically in a burst of pure, perfect tonal joy.

Rachmaninoff’s work is known to prominently feature impossibly dense, lush orchestration, in addition to an arresting empathy and a profundity of emotion. It is in this regard that he distinguished himself from contemporaries such as Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and Stravinsky; Rachmaninoff’s writing clung for dear life to the Romantic tradition in Russian music, even as it was inevitably borne toward the modern later in his work.

The Sonata in G minor for Cello and Piano, composed in 1901, is a remarkable example of this trend. While its outstanding feature in the repertoire is the fluidity and poignancy of its writing, which represents Romanticism at its best, it also evokes an intensely modern approach to composing still in the early stages of gestation.

The first movement of the sonata embodies the paradigmatic sonata form in many ways, but diverges notably in that the exposition introduces two different themes: one flowing, yet hesitant and quick to recoil, and the other one slower and more passionate. It is to the cascading, warm second theme that the sonata returns in its “recapitulation,” which follows a furious, virtuosic passage for both cello and piano.

The second movement is a scherzo in typical fashion, in which the primary cello theme is a descending minor scale. The introduction and recapitulation of the theme are bridged by an extended slow theme in A-flat major, which is accompanied by typical Rachmaninoff melodies in the piano part which loop over each other and draw exceedingly intricate lines.

The scherzo ends quietly and moves into the famous third movement, for which there are few words to describe quite what Rachmaninoff does. The third movement feels as if a profound expression of selfless love, in which the cello’s monophonic, trembling line rises above unfolding piano chords, each of which seems to swallow the last.

The sonata ends with the fourth movement, which is an energetic, whirling finale with many typical Rachmaninoff ornamentations. After a brief, slow retrospective, which fades nostalgically to nothing, the piece concludes by building in excitement and register until the final, sustained note.

About

Cellist and conductor Aster Zhang has performed as a soloist, chamber musician, and orchestral musician at venues across the nation and worldwide, including Carnegie Hall, the Tanglewood Music Festival, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the Liszt Academy, and the Vienna Musikverein. She is currently a cellist and conducting student in the Princeton University Orchestra, of which she has previously been principal cellist, as well as in Opus. She is an alumna of the Aspen Music Festival, the National Symphony Orchestra Summer Music Institute, in which she was a fellow and principal cellist, the Boston University Tanglewood Institute, and the Philadelphia International Music Institute, where she was a winner of the concerto competition.

Aster’s special interests include the Pokémon video game franchise, niche perfume, origami, pour-over coffee, long coats, and pasta. Her current independent research focuses are the multidimensional analysis of markets with certification intermediaries, fundamentals analysis of corporate fixed income markets, fraudulent trading in NFT markets, and femininity and gender performance in Russian opera.

Aster currently studies cello with Alberto Parrini and conducting with Michael Pratt at Princeton University, where she is a member of the Class of 2024 completing an A.B. in Economics with certificates in finance, cello performance, and conducting. This summer, she will study cello at the Chautauqua Institution School of Music with Felix Wang on scholarship. She has previously studied with Nayoung Baek, Darrett Adkins, Mihail Jojatu, Eugena Chang, Greg Beaver, and Tracy Sands.

I owe a great debt of thanks to the entire Department of Music at Princeton University for their support in making this recital a possibility for me; in particular, I thank Michael Pratt and Alberto Parrini for their support over the course of my time at Princeton, which made me the musician I am. I am moreover thankful to my good friends in Opus and the Princeton University Orchestra, who have made my time here meaningful. To Alexej, thank you. I love you. I make music for you.

Justine Langman is a sought-after collaborative pianist and chamber musician in the central NJ area. After graduating from Rutgers University in 2016 with her B.S. in Mathematics with High Honors, she began working as a staff pianist at the Mason Gross School of the Arts. Since then, she has collaborated and recorded with members of the New York Philharmonic, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Since 2020, Justine has served as the music director of United Reformed Church in Somerville, NJ, and she is currently the pianist for the Voorhees Choir and the University Choir at Rutgers. In 2023, Justine co-founded Parcae, a vocal trio which aims to make classical music a more immersive, accessible and inclusive art form by encouraging community participation. In her free time, Justine enjoys baking, rock-climbing, pickleball, and creating puzzles, murder mysteries and scavenger hunts for her friends.

Program Notes

J.S. Bach’s Suite No. 5 for Cello in C minor, the penultimate entry of his six revered dance suites for unaccompanied cello, is enigmatic: at once the culmination of the strikingly polyphonic melodic lines he had developed in his cello writing and also a complete musical departure of expression. Set in the intense, mournful key of C minor, and originally written in scordatura with the A string tuned a whole step down, the suite is permeated throughout with a lamenting air, suffused with warm and dark colors. Bach moves with seamless grace from burning anger to spirited dancing, and then overwhelming desolation.

The Prelude to the fifth Suite is unique among Bach’s six preludes for the cello in that it is bifurcated very clearly into two sections: a drawn-out, slow introduction in the style of a French overture and a fast-paced dance in triple meter. The former is rife with melisma, cascading up and down the cello’s lower ranges; it distinguishes itself from the other preludes in Bach’s oeuvre, many of them fast-paced and relentlessly modulatory, in its willingness to dwell in the key of C minor at a tempo reminiscent of a funeral dirge. Towards the end of the first section, the cello has an extended melismatic passage which completes the modulation in the “overture” into G minor, a brighter key that better-serves the dance to follow.

The second section is written entirely as a fugue in the form of a dance. The cello handles both the melodic line and its counterpoint in turn, rapidly alternating between the two. Readily apparent in the fugue is the use of sequential phrases, where a phrase of interest is repeated in a “sequence” of different keys, often in order to build anticipation for a dramatic re-statement of the subject. Perhaps most remarkable, an outlier among his cello work, is Bach’s usage of an adjacent open string, often the dominant tone in the key being played, to build volume, intensity, and tension.

The dance gradually grows in fervor and intensity before abruptly derailing; finding its footing once again, the line reaches a fever pitch with punctuated chords before ending on an incandescent, strikingly joyful Picardy third. PROGRAM NOTES By Aster Zhang ’24 The 20th-century cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was the sole primary force shaping much of how his contemporary composers and musicians approached the cello as an instrument. His famous virtuosity and uncompromising approach to musical interpretation influenced a generation of cellists, as well as a generation of composers.

The 3 Strophes sur le nom de Sacher, composed in 1976, exemplify Rostropovich’s influence at a remarkably large scale. They represent Henri Dutilleux’s contribution to a cycle of 12 pieces for unaccompanied cello in commemoration of the 70th birthday of conductor Paul Sacher. All twelve of the pieces in this cohort have the feature of drawing their theme from the note names corresponding to the letters in “Sacher”: E-flat, A, C, B, E, D.

Sacher develops this theme over the course of three “stanzas”. The first seems to meander across different manifestations and statements of the theme. It begins with a jolting, wary stutter: an E-flat, which dies down; then an E-flat followed by an A, which fades faster than it entered. Abruptly, the name in its full spelling spills out with astonishing rapidity, as if said in a hurry, a panic. Dutilleux sweeps in this movement from left to right in the letters of Sacher’s name, then from right to left; then, skipping back and forth with haphazard, reckless steps. The movement quotes from Bela Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, a notable work commissioned by Sacher, and then fades away.

The second stanza has the air of a nocturne, evoking in its sparse but deft use of the cello in its entirety works by Dutilleux’s contemporary Hans Werner Henze. Left-hand pizzicato, polyphonic with long bowed phrases which evoke hints of tonality, drive carried-over notes and Dutilleux explores the stratospheric ranges of the cello with rarely-played harmonics on the G and C strings. The transition to the third stanza is abrupt, following a held-out A harmonic marked “longa”. The cello launches into the last third of the piece with rapid restatements of Sacher’s melody at a whispering dynamic. At the climactic moment of the piece, the cello screams Sacher’s name at its highest possible dynamic and register unendingly, faster and faster, before choking on silence. After regaining its senses, the cello races toward the end at a breakneck pace, ending dramatically in a burst of pure, perfect tonal joy.

Rachmaninoff’s work is known to prominently feature impossibly dense, lush orchestration, in addition to an arresting empathy and a profundity of emotion. It is in this regard that he distinguished himself from contemporaries such as Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and Stravinsky; Rachmaninoff’s writing clung for dear life to the Romantic tradition in Russian music, even as it was inevitably borne toward the modern later in his work.

The Sonata in G minor for Cello and Piano, composed in 1901, is a remarkable example of this trend. While its outstanding feature in the repertoire is the fluidity and poignancy of its writing, which represents Romanticism at its best, it also evokes an intensely modern approach to composing still in the early stages of gestation.

The first movement of the sonata embodies the paradigmatic sonata form in many ways, but diverges notably in that the exposition introduces two different themes: one flowing, yet hesitant and quick to recoil, and the other one slower and more passionate. It is to the cascading, warm second theme that the sonata returns in its “recapitulation,” which follows a furious, virtuosic passage for both cello and piano.

The second movement is a scherzo in typical fashion, in which the primary cello theme is a descending minor scale. The introduction and recapitulation of the theme are bridged by an extended slow theme in A-flat major, which is accompanied by typical Rachmaninoff melodies in the piano part which loop over each other and draw exceedingly intricate lines.

The scherzo ends quietly and moves into the famous third movement, for which there are few words to describe quite what Rachmaninoff does. The third movement feels as if a profound expression of selfless love, in which the cello’s monophonic, trembling line rises above unfolding piano chords, each of which seems to swallow the last.

The sonata ends with the fourth movement, which is an energetic, whirling finale with many typical Rachmaninoff ornamentations. After a brief, slow retrospective, which fades nostalgically to nothing, the piece concludes by building in excitement and register until the final, sustained note.

About

Cellist and conductor Aster Zhang has performed as a soloist, chamber musician, and orchestral musician at venues across the nation and worldwide, including Carnegie Hall, the Tanglewood Music Festival, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the Liszt Academy, and the Vienna Musikverein. She is currently a cellist and conducting student in the Princeton University Orchestra, of which she has previously been principal cellist, as well as in Opus. She is an alumna of the Aspen Music Festival, the National Symphony Orchestra Summer Music Institute, in which she was a fellow and principal cellist, the Boston University Tanglewood Institute, and the Philadelphia International Music Institute, where she was a winner of the concerto competition.

Aster’s special interests include the Pokémon video game franchise, niche perfume, origami, pour-over coffee, long coats, and pasta. Her current independent research focuses are the multidimensional analysis of markets with certification intermediaries, fundamentals analysis of corporate fixed income markets, fraudulent trading in NFT markets, and femininity and gender performance in Russian opera.

Aster currently studies cello with Alberto Parrini and conducting with Michael Pratt at Princeton University, where she is a member of the Class of 2024 completing an A.B. in Economics with certificates in finance, cello performance, and conducting. This summer, she will study cello at the Chautauqua Institution School of Music with Felix Wang on scholarship. She has previously studied with Nayoung Baek, Darrett Adkins, Mihail Jojatu, Eugena Chang, Greg Beaver, and Tracy Sands.

I owe a great debt of thanks to the entire Department of Music at Princeton University for their support in making this recital a possibility for me; in particular, I thank Michael Pratt and Alberto Parrini for their support over the course of my time at Princeton, which made me the musician I am. I am moreover thankful to my good friends in Opus and the Princeton University Orchestra, who have made my time here meaningful. To Alexej, thank you. I love you. I make music for you.

Justine Langman is a sought-after collaborative pianist and chamber musician in the central NJ area. After graduating from Rutgers University in 2016 with her B.S. in Mathematics with High Honors, she began working as a staff pianist at the Mason Gross School of the Arts. Since then, she has collaborated and recorded with members of the New York Philharmonic, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Since 2020, Justine has served as the music director of United Reformed Church in Somerville, NJ, and she is currently the pianist for the Voorhees Choir and the University Choir at Rutgers. In 2023, Justine co-founded Parcae, a vocal trio which aims to make classical music a more immersive, accessible and inclusive art form by encouraging community participation. In her free time, Justine enjoys baking, rock-climbing, pickleball, and creating puzzles, murder mysteries and scavenger hunts for her friends.