Please consult our COVID-19 policies and resources for guidance on attending public performances.

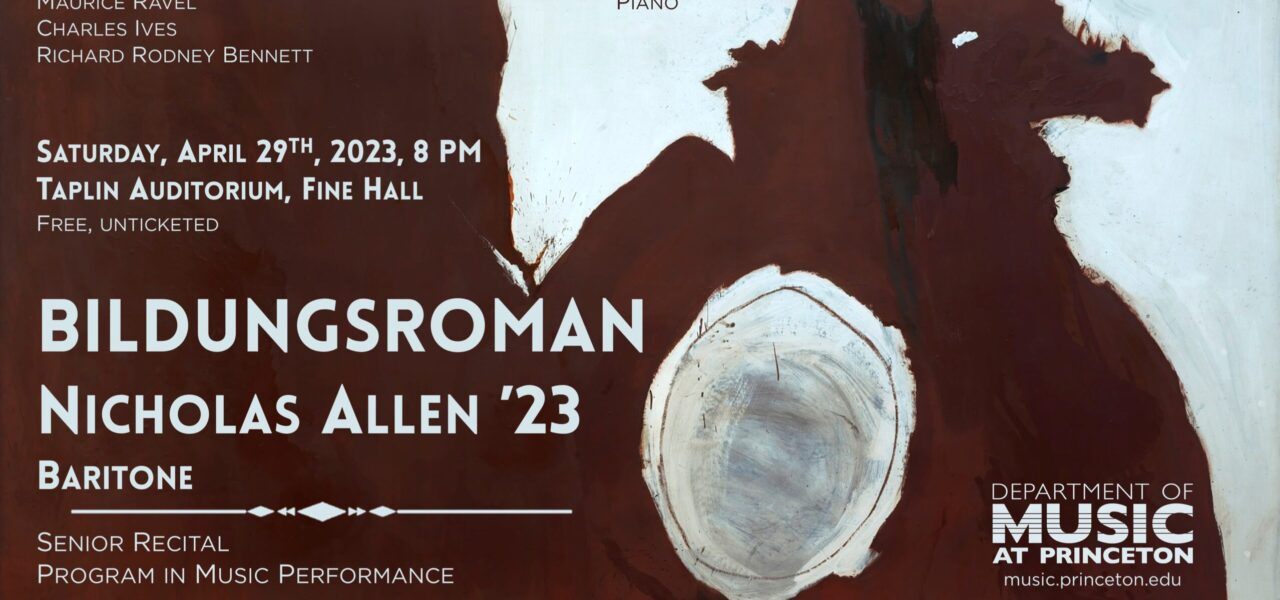

Certificate Recital: Nicholas Allen, Voice

Presented by Princeton University Music Department

date & time

Sat, Apr 29, 2023

8:00 pm - 9:00 pm

ticketing

Free, unticketed

- This event has passed.

Nicholas Allen ’23 (Voice) performs a senior recital.

Baritone

Bildungsroman

Songs of innocence and grief

Featuring:

Julia Hanna, piano

Program

RICHARD RODNEY BENNETT (1936—2012) Songs Before Sleep (2002)

KURT WEILL (1900—1950) Four Walt Whitman Songs (1942/1947)

MAURICE RAVEL (1875—1937) Histoires naturelles (1906)

CHARLES IVES (1874—1954) Selections from 114 Songs (1887-1921)

PROGRAM NOTES

RICHARD RODNEY BENNETT (1936–2012)

Songs Before Sleep (2002)

Sir Richard Rodney Bennett had the luck — rare in the 20th century — to be born into a family of classical

musicians whose daily life revolved around music making. And in certain ways his output of solo songs with

piano seems to perpetuate that childhood world in his cleaving to proverbial rhymes and satirical games rather

than texts of deep romantic introspection, and in his preference for generic musical forms and styles rather

than radical innovation. Because he has preferred to work with many singers of different kinds rather than

developing a life-long partnership with one, his output harbors no unified body of song such as we find in the

work of Poulenc or Britten. What it offers, by contrast, is a glittering array of styles prompted by the many

friendships and occasions, often domestic, for which he has composed, and characterized by the seemingly

effortless professionalism with which that early start imbued every aspect of his multifarious musical life.

These six songs were commissioned jointly by BBC Radio 3 and the Royal Philharmonic Society as part of the

New Generation Artists scheme, and first performed by their dedicatee, the bass-baritone Jonathan Lemalu

with Michael Hampton at the 2003 Spitalfields Festival. Bennett credits the title and explanation of the ditties

and nonsense poems drawn from the Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes to his sister, the writer Meg

Peacocke. Although some of the poems, such as Jane Taylor’s Twinkle, twinkle, little star have acquired

traditional tunes, Bennett comes up with melodies of his own throughout. As usual in his song writing, he

prefers to sustain, or to cross-cut, appropriate textures throughout each setting rather than continually to turn

aside for detailed “word-painting” — so that, for instance, the bleak propositions of As I walked by myself are

underpinned by an even pacing of quarter-notes throughout. The only exceptions are the more capricious

setting of Wee Willie Winkie, and the composite set of There was an old woman rhymes comprising the knees-

up finale.

— Bayan Northcott (2010)

KURT WEILL (1900–1950)

Four Walt Whitman Songs (1942/1947)

Walt Whitman’s collection of poems Drum-Taps, published in 1865 as the American Civil War was coming to

an end, according to Lawrence Kramer “helped to create a new, modern poetry of war, a poetry not just of

patriotic exhortation but of somber witness.” That modern aspect may be one reason why Whitman appealed

to so many German composers in the following century, especially exiles from the Third Reich. One such was

Kurt Weill, who in late 1941, in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, returned to Whitman’s collection Leaves of

Grass, which he had first encountered in the 1920’s. He quickly composed what were published as the Three

Walt Whitman Songs in 1942. Then, after a trip to Europe, he expanded the collection in 1947 to Four Walt

Whitman Songs with the addition of Come Up from the Fields, Father (an orchestral version was devised

subsequently). Weill’s wife, the singer Lotte Lenya, told him that the Walt Whitman Songs were “the best and

most effortless songs you have ever written,” but they received no public performances in his lifetime.

The problem, according to some commentators, was the way they blurred the boundaries of popular and

cultivated, or maybe American and European styles (although that seems little different from the rest of Weill’s

oeuvre); or, that, in the songs’ original order, Weill seems to read Whitman’s verses as pro-war when they

were anything but. When they were re-ordered in 1947, however, a more convincing narrative was constructed

that stressed the futility of fighting: beginning with a vigorous but ominous call-to-arms (Beat! Beat! Drums!),

then a lament for the ship’s captain’s death (O Captain! My Captain), followed by the tragic narrative of

informing those back home of their son’s death and the mother’s ensuing grief (Come Up from the Fields,

Father) and, finally, a dirge for not only the son but the father too (Dirge for Two Veterans).

— Laura Tunbridge (2018)

MAURICE RAVEL (1875–1937)

Histoires naturelles (1906)

In all Ravel’s output, his songs are perhaps the least appreciated genre. Why this is so remains something of a

mystery, but it could stem from his refusal to repeat himself, so that there is nothing we can call a typical Ravel

song. Of course this refusal applies to every other aspect of his work, but is there something in the psyche of

music lovers that prefers songs to be ever so slightly predictable?

With this group of songs, Histoires naturelles on prose poems by Jules Renard, Ravel’s playfulness tipped

over into controversy and the premiere in January 1907 was a noisy affair. His chief crime was to eliminate

some of the final mute ‘e’s, in the popular style of the café concert. In the opening Le paon, the peacock’s

pomposity is undercut by the shortening of “la fi-an-cé-e n’ar-ri-ve pas” to “la fian-cé’ n’ar-riv’ pas.” There was

even shouting when, in Le grillon, as the cricket took a rest (“Il se repose”) Ravel’s music came to a sudden

halt. Equally disconcerting, after the busy-busy movements of the cricket (which some commentators have

likened to Ravel himself), is the magical, visionary epilogue in D flat major, where he later admitted he had

deliberately allowed his Romantic inclinations to surface. Debussy, who by 1907 was no longer a friend,

complained of the “factitious Americanism” of the more light-hearted passages in the cycle, but even he had to

admit Le cygne was beautiful music. The piano part is marked “very gentle and enveloped in pedal” and the

setting of seven sixteenths in the right hand against two in the left makes for effortless progress, quite different

from the cricket’s precise gestures. Ravel dedicated the song to Misia Godebska, a mover and shaker in

Parisian musical circles who was soon to become Diaghilev’s right-hand woman, and it could be that Ravel

saw her as the swan, gliding smoothly through society with her eye fixed on the main chance.

“Not a bite, this evening,” complains the fisherman at the start of Le martin-pêcheur. The cool, diamond-like,

almost Messiaenic chords do not react (unlike the 1907 audience which here rose to an apogee of outrage)

but go their way “as slowly as possible.” Here is a music of silence, the singer somehow conveying

breathlessness while breathing deeply. Pierre Bernac called it “the most difficult mélodie of the set.” But for the

pianist the worst moments come in La pintade. With its gruppetti and shrill, explosive acciaccaturas, it looks

back not just to Alborada del gracioso but to another fowl-piece, “Baba-Yaga” from Mussorgsky’s Pictures at

an Exhibition. It makes an entertaining and aesthetically uncomplicated finale to the set, but also displays

Ravel’s aggressive side.

— Roger Nichols (2009)

CHARLES IVES (1874–1954)

Selections from 114 Songs (1887–1921)

Ives wrote songs through his entire creative life — from Slow March for the funeral of the family cat (probably

1887) to In the Mornin’ (1930), a setting of the Negro spiritual Give me Jesus!. This aspect of his art brings us

closer than any other to his emotional core. In all he composed around two hundred songs — far more than

the famous collection of 114 Songs he published privately in 1922.

Remembrance (1921) was written in 1906 as a “song without voice” for cornet and chamber ensemble called

The Pond. Ives once called it an “obvious picture,” and it is an elegy for his father — buried at Wooster

Cemetery in his home town of Danbury, CT (where the pond in question lies) — whose expressive cornet-

playing was always an abiding memory. The cornet has the main melody, and Ives put words to it on the score.

In 114 Songs, he gave these words to the singer, adding a superscription — two lines by Wordsworth: “The

music in my heart I bore / Long after it was heard no more.”

The Things Our Fathers Loved (1917), subtitled “(and the greatest of these was Liberty)”, is one of Ives’s

greatest songs, one of his crucial statements about what his music is about, and typically woven from a

veritable tapestry of quotations of tunes, including “Dixie,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” “The Battle Cry of

Freedom” and “In the sweet Bye and Bye.” The date of composition is significant: Ives thought it was important

to remember the values he felt were enshrined in these melodies, as America entered the Great War. Another

and more explicit “war song” from 1917 – though entirely unwarlike in character — is Tom Sails Away. Here

the hallucinatory textures create a haze of childhood memories, shadowed by the consciousness of war in

Europe. The popular song “Over there” is referred to in the music, along with “Araby’s daughter” and Ives’s

great favorite, “Columbia, the Jewel of the Ocean.” The elegiac close suggests that the kid brother who has

enlisted and taken ship for “over there” will not return.

At the River is dated 1916; the text and basic tune come from the revivalist hymn by Robert Lowry, now

famous from the setting in Aaron Copland’s Old American Songs. Ives arranged this song from the second

movement of his Violin Sonata No. 4; there may have been an earlier version for cornet and violins. Note the

very free accentuation of the words, which causes the song to end with an “unanswered question” of its own.

Evidence is dated 1910, but here Ives had substituted his own words to what was a much earlier setting (about

1898) of the poem “Wie Melodien zieht es mir” by Klaus Groth (also set by Brahms, in his Op. 105). In this lyric

landscape, the onset of night is symbolized in the voice’s drooping, descending phrases.

Songs My Mother Taught Me was written in 1895: the text is a translation by Natalie Macfarren of the Czech

poem by Adolf Heyduk that had already been set (rather famously) by Dvořàk. Around 1903 Ives made a

chamber ensemble version of this song under the title An Old Song Deranged — in his “psychological

biography” of Ives, Stuart Feder takes this to imply that Ives’s mother Mollie could have suffered from

dementia, but there is no hard evidence: the title may have been a passing word-play.

— Calum MacDonald (2008)

ABOUT

NICHOLAS ALLEN ’23

BARITONE

Nicholas Allen is a baritone and composer from the Princeton Class of 2023,

concentrating in Computer Science (B.S.E.) with certificates in Engineering Physics

and Vocal Performance. Growing up in Alexander, NY, he took an interest in vocal

and choral music from a young age, performing as a soloist with the NAfME All-

National Honor Ensemble Mixed Choir under the direction of Dr. Amanda Quist. At

Princeton, Nicholas studies voice in the studio of Dr. Christopher Arneson, while

also performing and touring with both the Princeton Glee Club and Chamber Choir

under the direction of Gabriel Crouch. After completing his bachelor’s degree, he

plans on working as a research scientist and software engineer at IBM Quantum,

with plans to later attend graduate school to study quantum computing.

JULIA HANNA

PIANO

Julia Hanna has performed widely in the New York and Philadelphia metropolitan

areas, building an extensive repertoire of solo and chamber music. Currently, she

serves as a coach and accompanist at Westminster Choir College. As an

accompanist she has also performed and toured with several choirs from the New

York area, in which capacity the New York Times has praised her performances as

“vivid” and “deft.” In 2018 Julia was honored to be a featured performer in a Philip

Glass opera workshop in North Adams, MA.

PROGRAM NOTES

RICHARD RODNEY BENNETT (1936–2012)

Songs Before Sleep (2002)

Sir Richard Rodney Bennett had the luck — rare in the 20th century — to be born into a family of classical

musicians whose daily life revolved around music making. And in certain ways his output of solo songs with

piano seems to perpetuate that childhood world in his cleaving to proverbial rhymes and satirical games rather

than texts of deep romantic introspection, and in his preference for generic musical forms and styles rather

than radical innovation. Because he has preferred to work with many singers of different kinds rather than

developing a life-long partnership with one, his output harbors no unified body of song such as we find in the

work of Poulenc or Britten. What it offers, by contrast, is a glittering array of styles prompted by the many

friendships and occasions, often domestic, for which he has composed, and characterized by the seemingly

effortless professionalism with which that early start imbued every aspect of his multifarious musical life.

These six songs were commissioned jointly by BBC Radio 3 and the Royal Philharmonic Society as part of the

New Generation Artists scheme, and first performed by their dedicatee, the bass-baritone Jonathan Lemalu

with Michael Hampton at the 2003 Spitalfields Festival. Bennett credits the title and explanation of the ditties

and nonsense poems drawn from the Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes to his sister, the writer Meg

Peacocke. Although some of the poems, such as Jane Taylor’s Twinkle, twinkle, little star have acquired

traditional tunes, Bennett comes up with melodies of his own throughout. As usual in his song writing, he

prefers to sustain, or to cross-cut, appropriate textures throughout each setting rather than continually to turn

aside for detailed “word-painting” — so that, for instance, the bleak propositions of As I walked by myself are

underpinned by an even pacing of quarter-notes throughout. The only exceptions are the more capricious

setting of Wee Willie Winkie, and the composite set of There was an old woman rhymes comprising the knees-

up finale.

— Bayan Northcott (2010)

KURT WEILL (1900–1950)

Four Walt Whitman Songs (1942/1947)

Walt Whitman’s collection of poems Drum-Taps, published in 1865 as the American Civil War was coming to

an end, according to Lawrence Kramer “helped to create a new, modern poetry of war, a poetry not just of

patriotic exhortation but of somber witness.” That modern aspect may be one reason why Whitman appealed

to so many German composers in the following century, especially exiles from the Third Reich. One such was

Kurt Weill, who in late 1941, in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, returned to Whitman’s collection Leaves of

Grass, which he had first encountered in the 1920’s. He quickly composed what were published as the Three

Walt Whitman Songs in 1942. Then, after a trip to Europe, he expanded the collection in 1947 to Four Walt

Whitman Songs with the addition of Come Up from the Fields, Father (an orchestral version was devised

subsequently). Weill’s wife, the singer Lotte Lenya, told him that the Walt Whitman Songs were “the best and

most effortless songs you have ever written,” but they received no public performances in his lifetime.

The problem, according to some commentators, was the way they blurred the boundaries of popular and

cultivated, or maybe American and European styles (although that seems little different from the rest of Weill’s

oeuvre); or, that, in the songs’ original order, Weill seems to read Whitman’s verses as pro-war when they

were anything but. When they were re-ordered in 1947, however, a more convincing narrative was constructed

that stressed the futility of fighting: beginning with a vigorous but ominous call-to-arms (Beat! Beat! Drums!),

then a lament for the ship’s captain’s death (O Captain! My Captain), followed by the tragic narrative of

informing those back home of their son’s death and the mother’s ensuing grief (Come Up from the Fields,

Father) and, finally, a dirge for not only the son but the father too (Dirge for Two Veterans).

— Laura Tunbridge (2018)

MAURICE RAVEL (1875–1937)

Histoires naturelles (1906)

In all Ravel’s output, his songs are perhaps the least appreciated genre. Why this is so remains something of a

mystery, but it could stem from his refusal to repeat himself, so that there is nothing we can call a typical Ravel

song. Of course this refusal applies to every other aspect of his work, but is there something in the psyche of

music lovers that prefers songs to be ever so slightly predictable?

With this group of songs, Histoires naturelles on prose poems by Jules Renard, Ravel’s playfulness tipped

over into controversy and the premiere in January 1907 was a noisy affair. His chief crime was to eliminate

some of the final mute ‘e’s, in the popular style of the café concert. In the opening Le paon, the peacock’s

pomposity is undercut by the shortening of “la fi-an-cé-e n’ar-ri-ve pas” to “la fian-cé’ n’ar-riv’ pas.” There was

even shouting when, in Le grillon, as the cricket took a rest (“Il se repose”) Ravel’s music came to a sudden

halt. Equally disconcerting, after the busy-busy movements of the cricket (which some commentators have

likened to Ravel himself), is the magical, visionary epilogue in D flat major, where he later admitted he had

deliberately allowed his Romantic inclinations to surface. Debussy, who by 1907 was no longer a friend,

complained of the “factitious Americanism” of the more light-hearted passages in the cycle, but even he had to

admit Le cygne was beautiful music. The piano part is marked “very gentle and enveloped in pedal” and the

setting of seven sixteenths in the right hand against two in the left makes for effortless progress, quite different

from the cricket’s precise gestures. Ravel dedicated the song to Misia Godebska, a mover and shaker in

Parisian musical circles who was soon to become Diaghilev’s right-hand woman, and it could be that Ravel

saw her as the swan, gliding smoothly through society with her eye fixed on the main chance.

“Not a bite, this evening,” complains the fisherman at the start of Le martin-pêcheur. The cool, diamond-like,

almost Messiaenic chords do not react (unlike the 1907 audience which here rose to an apogee of outrage)

but go their way “as slowly as possible.” Here is a music of silence, the singer somehow conveying

breathlessness while breathing deeply. Pierre Bernac called it “the most difficult mélodie of the set.” But for the

pianist the worst moments come in La pintade. With its gruppetti and shrill, explosive acciaccaturas, it looks

back not just to Alborada del gracioso but to another fowl-piece, “Baba-Yaga” from Mussorgsky’s Pictures at

an Exhibition. It makes an entertaining and aesthetically uncomplicated finale to the set, but also displays

Ravel’s aggressive side.

— Roger Nichols (2009)

CHARLES IVES (1874–1954)

Selections from 114 Songs (1887–1921)

Ives wrote songs through his entire creative life — from Slow March for the funeral of the family cat (probably

1887) to In the Mornin’ (1930), a setting of the Negro spiritual Give me Jesus!. This aspect of his art brings us

closer than any other to his emotional core. In all he composed around two hundred songs — far more than

the famous collection of 114 Songs he published privately in 1922.

Remembrance (1921) was written in 1906 as a “song without voice” for cornet and chamber ensemble called

The Pond. Ives once called it an “obvious picture,” and it is an elegy for his father — buried at Wooster

Cemetery in his home town of Danbury, CT (where the pond in question lies) — whose expressive cornet-

playing was always an abiding memory. The cornet has the main melody, and Ives put words to it on the score.

In 114 Songs, he gave these words to the singer, adding a superscription — two lines by Wordsworth: “The

music in my heart I bore / Long after it was heard no more.”

The Things Our Fathers Loved (1917), subtitled “(and the greatest of these was Liberty)”, is one of Ives’s

greatest songs, one of his crucial statements about what his music is about, and typically woven from a

veritable tapestry of quotations of tunes, including “Dixie,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” “The Battle Cry of

Freedom” and “In the sweet Bye and Bye.” The date of composition is significant: Ives thought it was important

to remember the values he felt were enshrined in these melodies, as America entered the Great War. Another

and more explicit “war song” from 1917 – though entirely unwarlike in character — is Tom Sails Away. Here

the hallucinatory textures create a haze of childhood memories, shadowed by the consciousness of war in

Europe. The popular song “Over there” is referred to in the music, along with “Araby’s daughter” and Ives’s

great favorite, “Columbia, the Jewel of the Ocean.” The elegiac close suggests that the kid brother who has

enlisted and taken ship for “over there” will not return.

At the River is dated 1916; the text and basic tune come from the revivalist hymn by Robert Lowry, now

famous from the setting in Aaron Copland’s Old American Songs. Ives arranged this song from the second

movement of his Violin Sonata No. 4; there may have been an earlier version for cornet and violins. Note the

very free accentuation of the words, which causes the song to end with an “unanswered question” of its own.

Evidence is dated 1910, but here Ives had substituted his own words to what was a much earlier setting (about

1898) of the poem “Wie Melodien zieht es mir” by Klaus Groth (also set by Brahms, in his Op. 105). In this lyric

landscape, the onset of night is symbolized in the voice’s drooping, descending phrases.

Songs My Mother Taught Me was written in 1895: the text is a translation by Natalie Macfarren of the Czech

poem by Adolf Heyduk that had already been set (rather famously) by Dvořàk. Around 1903 Ives made a

chamber ensemble version of this song under the title An Old Song Deranged — in his “psychological

biography” of Ives, Stuart Feder takes this to imply that Ives’s mother Mollie could have suffered from

dementia, but there is no hard evidence: the title may have been a passing word-play.

— Calum MacDonald (2008)

ABOUT

NICHOLAS ALLEN ’23

BARITONE

Nicholas Allen is a baritone and composer from the Princeton Class of 2023,

concentrating in Computer Science (B.S.E.) with certificates in Engineering Physics

and Vocal Performance. Growing up in Alexander, NY, he took an interest in vocal

and choral music from a young age, performing as a soloist with the NAfME All-

National Honor Ensemble Mixed Choir under the direction of Dr. Amanda Quist. At

Princeton, Nicholas studies voice in the studio of Dr. Christopher Arneson, while

also performing and touring with both the Princeton Glee Club and Chamber Choir

under the direction of Gabriel Crouch. After completing his bachelor’s degree, he

plans on working as a research scientist and software engineer at IBM Quantum,

with plans to later attend graduate school to study quantum computing.

JULIA HANNA

PIANO

Julia Hanna has performed widely in the New York and Philadelphia metropolitan

areas, building an extensive repertoire of solo and chamber music. Currently, she

serves as a coach and accompanist at Westminster Choir College. As an

accompanist she has also performed and toured with several choirs from the New

York area, in which capacity the New York Times has praised her performances as

“vivid” and “deft.” In 2018 Julia was honored to be a featured performer in a Philip

Glass opera workshop in North Adams, MA.