The Princeton University Chamber Choir, joined by twenty-five alumni, recently made their mark at the National Collegiate Choral Organization (NCCO) biennial conference. Hosted at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, from November 9-11, the event was a milestone occasion for the choir, marking its first invitation to a major choral conference. Under the direction of Gabriel Crouch, Director of Choral Activities, the choir opened the closing concert with Poulenc’s Figure humaine, a piece as challenging as it is rewarding. In this interview, Gabriel Crouch delves into the intricacies of Poulenc’s choral masterwork, the journey of the choir from pandemic-era lockdown to its triumphant performance in spring 2022, and the profound impact of this experience on all involved.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

Gabriel, for readers unfamiliar with Poulenc’s Figure humaine, how do you describe this work?

Figure humaine is generally acknowledged to be Poulenc’s crowning achievement as a choral work, but funnily enough it’s the one that’s never heard, because it is such a heavy lift. Poulenc grew up in the Paris of Diaghilev and Stravinsky and tried very hard to be a modernist, but he soon realized he wasn’t that kind of composer: He’s a melodist, incredibly adept at bringing a kind of jazz harmony into his music, and very playful. The ‘choral composer’ incarnation of Francis Poulenc began in 1936 when a very close friend of his died, causing him to reset. Revisiting the Catholicism of his youth, he began hearing choir singing in his musical imagination, and by the early 1940s, he was thinking of himself as a “choral” composer and, in fact, was one of the very few composers of the 20th century who predominantly existed as such. Of course, war had by then broken out. Resistance to the creep of fascism across Europe took many forms. The Résistance was an iconic part of French identity, but the resistance was not just an armed struggle — it was also a cultural resistance. Poets were writing poetry, and musicians were composing music to contribute. Paul Éluard, one of the great French surrealist poets of the period, published a volume of poetry called Poésie et vérité 1942, of which the final and biggest poem in this collection, Liberté, became symbolic of the Resistance itself. The poem simply identifies objects in the universe — from the very local to the absolute macro — and imagines daubing them with this single word as a rejection of tyranny: liberté. It was actually dropped in leaflet form over France by the British Royal Air Force in an effort to embolden civilians and fighters. I mean, can you imagine? For Poulenc the musical setting of Éluard’s texts was his gesture of resistance.

“I mentioned the fact that Chamber Choir was singing at a conference to a friend and she immediately said, ‘gosh, it sounds like you signed up to be in this choir for life!’ And it’s true. This experience has been such a good example of how the music that we made during our time at Princeton stays with us well after we graduate. More importantly, however, it’s a wonderful reminder that the connections we formed at Princeton can and will stand the test of time and distance.” — Cat Keim (‘23)

Mary Lou Williams — composer of Black Christ of the Andes, which you and Chamber Choir would pair with Poulenc’s Figure humaine in performance — used to distribute leaflets at performances of her mass, which read, in all caps: “YOUR ATTENTIVE PARTICIPATION […] WILL ALLOW YOU TO […] REAP THE FULL THERAPEUTIC REWARDS THAT GOOD MUSIC ALWAYS BRINGS TO A TIRED, DISTURBED SOUL […].” Poulenc, of course, composed his Figure humaine amid WWII. Williams composed her mass amid the civil rights movement. I imagine you and the members of the choir found this music to be, to use Williams’ word, therapeutic when faced with a pandemic that not only forced you all into lockdown but also dashed hopes of a 2020 performance.

We hadn’t actually started work on the Mary Lou Williams by the time the pandemic hit. But those words ring very true in terms of what the performance experience felt like when we finally did sing Figure humaine in 2022. When that first concert had to be cancelled in 2020 I was totally heartbroken for the students. After some initial trepidation, they had really fallen head over heels in love with Figure Humaine, so they were all suddenly bereft without it. In a funny way, I feel like I got to know this group of students better than any I’ve ever known at Princeton. We talked so much, and so deeply, and so often. A lot of us got together regularly and talked about Figure humaine. I knew some of them were ‘up to stuff’: Charlie Hemler, who graduated in 2020, was doing all kinds of recording projects in his bedroom, and sometime in March 2020 he sent me a file of one of the movements of the piece where all of our Chamber Choir singers had sent in recordings and he had knitted them together. David Kim, also class of 2020, made his own exquisite rendering of the sixth movement for seven cellos. These were beautiful projects, yes, but more than that, to see that this was a high priority for students in the midst of everything they were going through in April 2020 was so very moving. So I was very determined that they would eventually get their chance to sing this piece, and also that when we did perform it, that we would weave in all this brilliant extra work the students had done. When we came back in Fall 2021 it was absolutely inevitable that everyone who’d since graduated, but who had put the hard yards in for the piece in the first place, would come back to do it with us. So really what that concert in 2022 felt like was firstly, a performance of Figure humaine and Black Christ of the Andes, but secondly, a meditation upon the process of making this concert happen. We included David’s piece, and we included a composition by Allison Spann ’20 that explored not only the connective tissue between the two pieces, but also what it is to assemble a community. There was also poetry reading in between the Poulenc movements. So it was both a performance of and a meditation upon the experience of preparing these pieces. Very cathartic!

“Grappling with the abrupt end of what was my first and only year in PUGC / Chamber Choir, I sought out some semblance of personal and artistic closure. I came across a rendition of Figure humaine by the 12 Cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic and, as a cellist myself, was inspired to create my own recording of the beautifully poignant sixth movement on the cello. Having had the chance to perform the piece not just once, but twice, I am deeply grateful and humbled for feeling the long-awaited closure and fulfillment of performing the piece most central and impactful to my choral experience at Princeton.” — David Kim (‘20)

Of course you wouldn’t have known that the world was about to be thrust into a global pandemic when you chose to program these works originally. What is your own history with Figure humaine and what led you to program it?

I’ve been obsessed with the piece for decades. I think my first experience with it was seeing the score and trying to ‘hear’ it on the page. But it was far too complicated. I was already crazy about Poulenc even as a kid — the piano music, the organ concerto which I absolutely adore, the harpsichord concerto — but I was never in a choral setting as a young singer where it would be possible to sing this one. The King’s Singers, which I sang in during my 20s, only had six voices, while Figure humaine requires fourteen. And growing up singing liturgical music in choirs, it didn’t fit the bill there either. But when I got to the end of my King’s Singers career in the early 2000s, I started nagging my friend Nigel Short, who’d established the choir Tenebrae, to get to know this piece. And Tenebrae, which I eventually joined, ended up performing it quite a lot, and when they recorded it, I wrote the liner notes. (I even wrote my Masters’ thesis on the piece, too!). When I moved to America in 2005, I was obsessed with idea of doing it one day. I began every single year of my teaching here by asking myself the question: could I program Figure humaine this year? And then I would think… don’t be greedy. It’s so important to remember that we are programming music for the nourishing experience of the students, and not for the pleasure, or vanity, of the conductor. It was 2019, nine years into my career at Princeton, when I felt like I could really say that, in terms of how the program had grown and how confident and self-assured the singers had become, we were ready to take it on.

“As we sang the last note of ‘Liberté’ in the Morehouse College auditorium, tears streamed down my face, and the realization of singing with the Princeton Chamber Choir for the last time in my life sunk in. It was an absolutely exhilarating and privilege I am so grateful to have had, and it’s hard to think of anything that could top this!” — Shruti Venkat (‘23)

Now, of course, you’re bringing the Chamber Choir, along with 25 alums of the choir, to sing Poulenc’s piece in the closing concert of the National Collegiate Choral Organization conference. How did this opportunity come about?

In my position, I am encouraged by the national choral federations — ACDA and NCCO — to apply to present our choirs at their conferences. But I’m always reluctant to put our students out there just for the sake of it. I believe very strongly that the most important work that we do happens during the three times each week when we get together to rehearse. That’s what the heart of my job is, and that’s why our students show up — to experience art together. But I was also aware that in our choral program we only get to perform our pieces once; and I knew that, for this piece, once isn’t really enough… and that students would respond positively if they suddenly had another opportunity to perform it. So, it was 11:30pm on the deadline day to submit recordings to NCCO, and I was sat at home waiting for my wife (who is, amongst other things, the manager of the Philadelphia Orchestra’s Symphonic Chorus) to come home from Philadelphia, where she’d been overseeing a concert. All of a sudden, I became possessed with the idea that I should apply to present Figure Humaine with the Chamber Choir, so of course a huge panic set in. The paperwork is lengthy: you have to submit up-to-date bios, recordings — not just half an hour of singing, but three separate tracks from three separate years that can’t be longer than around two minutes — and I’m terrible at this sort of thing! Meanwhile the clock was ticking. Christie walked through the door at about two minutes to midnight, at which point I should have said, “hello, darling, welcome home, it’s so nice to see you again,” but instead I said, “darling, hold on, I’ve got 90 seconds!” I literally submitted it in that last minute before midnight on deadline day, all because of a sudden revelation 30 minutes earlier.

And then presumably you had to wait.

I didn’t tell anyone I’d applied and just forgot about it, until sometime in June. Christie and I were at a hardwood floor showroom on Route 1. We’d gotten some samples, carried them back to the car, and in that awful modern way that we do before we start driving, I checked my phone… which is when the email popped up: “Congratulations! Your choir has been successful in its application to perform at NCCO.” So of course I was elated, but then, quite soon after, I started thinking, well, how are we actually going to do this? We can’t start rehearsing until mid September, and this performance is on November 11th. At this point I have hardly any veterans from that 2022 performance in the student body, so I now have to teach this piece in less than two months to an entirely new crew of singers. And we have other programming scheduled already. The NCCO also asked me not to tell anybody, so I had to write back to them and say, well, I really can’t not tell the singers. So they said, fine, but on pain of death that they can’t broadcast this publicly. So it was a thrilling moment when I could finally assemble an email list of all the students who’d done the piece in 2022 and congratulate them, because their performance of the piece in 2020 is what earned us this wonderful honor. And a flood of overjoyed responses came in. I thought maybe half of the alums would come back, but I think 25 out of 27 are returning, from as far as Edinburgh UK. It’s quite something.

Returning to the piece again in 2023, what do rehearsals look like, both for the current members of the Chamber Choir and for the 25 alums from the classes of 2020-2023 who will be traveling to Atlanta for the performance?

None of these folks are musicians; they’re all working nine-to-fives. So I knew we would have to rehearse intensively, and only once. The opportunity presented itself on the weekend before the NCCO conference, which has just passed; it was ‘football concert weekend’ where our Glee Club hosts the Yale Glee Club. So our Chamber Choir alums gathered together with the current choir to rehearse for several hours on Saturday and several more on Sunday, and we also sang part of the piece at the football concert on Saturday night. The good thing is that because it takes so much effort to learn Figure humaine in the first place, the muscles are very thoroughly trained, and they can be quite easily reactivated on returning to the piece. I think that most of our alums were pretty happy to see how quickly it came back into their voices.

“Poulenc begins his piece by declaring, ‘Of all springs in the world, this is the ugliest.’ When COVID hit in the spring of 2020, the words seemed nearly prophetic. Now, four years after I first started the piece, the painful delay only intensified the hope that runs throughout the piece alongside the suffering.” — Charlie Hemler (‘20)

What do you hope the students will take from this experience?

One of the things that Princeton is both blessed with and hamstrung by is the fact that we have a sort of built-in, very warm, very bountiful audience of students, faculty, parents, and a lot of alums. But this can ringfence what we do from the rest of the world if we’re not careful. And one of the consequences of this as well is that when we do have special art-making experiences here, it’s sometimes quite hard for a student to understand just how unusual it actually is or how rare their achievement might be. Something I hear from alumni in the years following their graduation: I didn’t realize at the time what a special orchestra I was playing in or what a wonderful choir I was singing in. So this NCCO conference is an opportunity for our students to understand that in the most rarefied air of the collegiate choral world, which is what NCCO represents, what they’ve achieved with Figure humaine is extraordinary. And I hope that this will help them understand the value of the time that they’ve put in and to feel fortified by it — to be able to meditate upon this experience and look back on it in the future as well. And, of course, I’d love for the recording that will be made at the conference, of which they’ll all get a copy, to be something for them to treasure. I’m also hoping that they will perhaps be able to take in the entirety of Figure humaine a little bit more now that they’re coming to the piece a second time.

And the audience of conference delegates, your colleagues, what do you hope they will take from this music?

Putting the program together for this concert, I mused on how special it is that we are a choir of volunteers. That is not the typical university choral experience in America, where singers are there for credit. So at this NCCO concert, there will be all of these Princeton students onstage who’ve all done these months of work without earning a penny or a credit for it. They’ve simply shown up for each other and for the music. I hope that that is edifying and encouraging for the choral community, especially in this moment where we’re all building our programs back again after the pandemic. Hopefully a feel-good story for the conference…

Might we see a visit from the Morehouse College Glee Club or any of the choirs participating in the weekend’s events to Princeton’s campus in the future?

Everyone knows the Morehouse Glee Club from its legendary appearances at great civic events in American history (such as JFK’s funeral), but the modern choral community also reveres the choir because of its director, Dr David Morrow — one of the great figures in our industry. I’m very keen to build a deep connection with the choir in the future and I plan to invite them to campus in 2025…

If you could leave us with a few parting words or a snippet of music, which words or section of Figure humaine would you leave us with?

It would be the end of the seventh movement, for both textual and musical reasons. The movement is called, La menace sous le ciel rouge, or the evil under the red sky, and it’s terrifying. The text alone is gruesome, but it also contains one of the hardest fugues that I’ve ever seen in a score. So it begins with about 90 seconds of fugal terror, and then suddenly a pivot point in the middle, with the suggestion that the earth might somehow be big enough and powerful enough to absorb, and recover from the poison of fascism. And as we get closer to the end, there begins a sort of yell — and by the end, the singers are really yelling — about the indestructible essence of humanity. But getting to that final yell takes several minutes, and begins with an incredibly soft, beautiful bed of oscillating harmony. I’m sure, if you asked all the singers to name their favorite bit, most would say ‘the second half of the seventh movement.’ It is the most magical choral writing, and uniquely and unmistakably Poulenc. I can barely talk about it without tearing up. It is also the moment where a first suggestion of reprieve is hinted at, and where the reassertion of our humanity in the text starts to appear. I’ve been in floods of tears at many points in the singing of that movement, both in my time as a singer and also as a conductor. It is incredibly powerful music. It’s one of the best two minutes you’ll ever experience.

In Other News

Resonant Revival: How a Norwegian Folk Fiddle Found a New Voice at Princeton

May 19, 2025

Dan Trueman, Chair of the Music Department, introduces Norwegian folk instruments to a new generation of composers and performers.

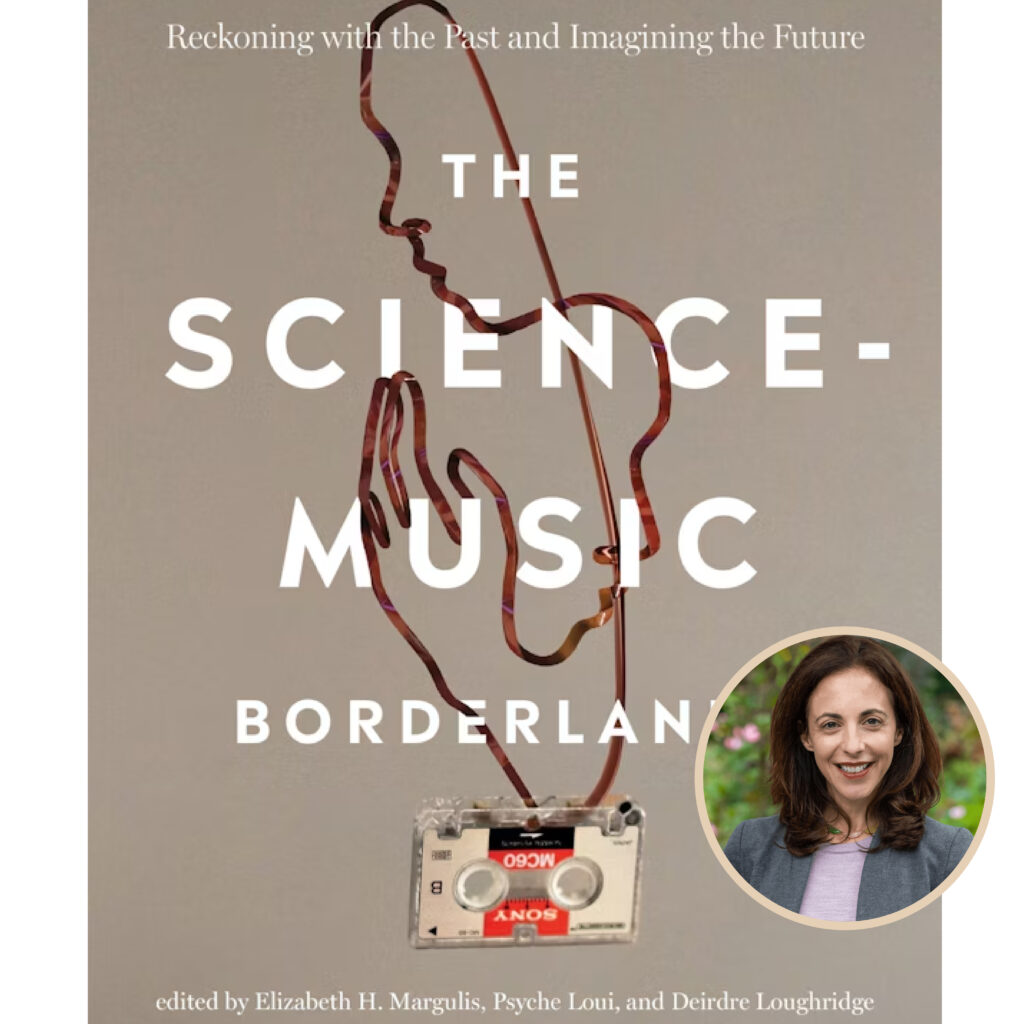

Elizabeth Margulis on the Frontiers of Music Cognition

Jan 22, 2025

The Department of Music is thrilled to congratulate musicology professor and Director of Graduate Studies Elizabeth Margulis, who has received the Ruth A. Solie Award for her editorial contributions to The Science-Music Borderlands: Reckoning with the Past and Imagining the Future.

Announcing the Launch of Princeton in Leipzig

Jan 7, 2025

Enrollment in “Princeton in Leipzig” has been extended to March 2, 2025! The Princeton Music Department is excited to announce the launch of Princeton in Leipzig, a summer study abroad …