Presenting the Electrosteel at New Interfaces for Musical Expression & mixing a new record of electronic dance music.

In 2012, Director of Electronic Music & PLOrk Jeffrey Snyder sent an email to a group of pedal steel guitar players. He’d had a kind of radical idea: could he apply the particular design, or interface, of the pedal steel guitar to the concept of the synthesizer, creating a brand new electronic instrument that expands the expressive possibilities of live synthesizer performance?

“A lot of people over the years have been trying to figure out new ways that we can control electronics. The keyboard synth isn’t the only way — just like the computer mouse isn’t the only way to control a computer — it’s just been the most commercially successful way.”

Evolving out of the lap steel guitar, also known as Hawaiian guitar, the pedal steel incorporates elements of the concert harp such as, well, pedals (along with knee levers) to selectively stretch and alter the tuning of the strings, thereby enabling a pedal steel player to change chords with much more variety and ease than on a traditional lap steel. It’s a sort of weird mechanical contraption that looks very much of its time — circa 1950s — with a devoted following in two genres: country music and the gospel tradition Sacred Steel.

“The first half of the 20th century had a Hawaiian craze that ended up producing a solid crop of steel guitarists in America by the 1950s. Slide guitar ended up in country music mostly because Jimmie Rogers hired Hawaiian players to play with him, and there was an industry of people going door-to-door to offer Hawaiian guitar lessons in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s.”

Ten years later, after a humbling 7 years spent learning to play the instrument and a further 5 years testing, prototyping, and iterating, Snyder’s invention has finally come to fruition. This summer, he will present the Electrosteel at the New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME) conference in Mexico City.

Snyder’s work in the Music Department sits at the intersection of arts and engineering. He works on topics of new instrument design, alternate tunings, composition, robotics, and networked performance practices. The Electrosteel is not the first instrument Snyder has designed — his “Manta,” designed between 2007- 2009 has taken on a sort of life of its own, with an impressive and devoted following — but it was the most challenging.

“With the Electrosteel, I wanted to balance having it feel as much like a pedal steel as possible while also not copying things about the interface that were unnecessary or expensive. I wanted to reduce the pedal steel down to the essentials.”

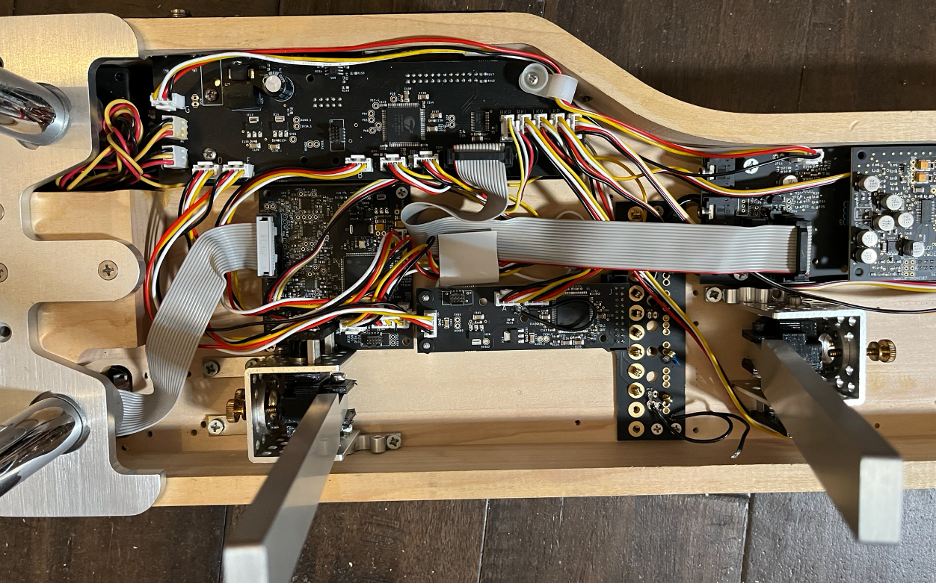

In the course of proof of concept experiments (performed with the help of undergraduate student researchers including Class of 2018’s Jonathan Zong, who is now studying human-computer interaction at MIT, and Class of 2019’s Matt Wang, who has just finished an MFA in game design at NYU) and prototyping, Snyder discovered that some of the more elegant (and, sadly, cost effective) solutions he’d originally planned just weren’t going to make for a satisfying player experience. He’d planned to simplify the knee levers of the pedal steel, for example, by replacing them with optical sensors that would sense the player’s knee position, eliminating the need for physical contact; but the lack of feedback proved unrewarding. “There’s something attractive about contact-free performance,” he explains. “The theremin is so cool, but it is hard to play and that’s because you’re just flying around in space, never getting any feedback. There aren’t many theremin virtuosos.” Snyder experimented for a time with 3D printed parts, too, only to realize they’d break under the stresses the instrument is subjected to. “There’s a reason everything on a pedal steel is made out of aluminum and chrome steel. You’re stomping on stuff and you have to push the levers pretty hard.” If the instrument itself is too light, it breaks.

“In my opinion, if you make an instrument and nobody plays it, it’s not an instrument”

The Electrosteel that Snyder will present this summer at NIME isn’t perfect, but it’s pretty close to his current goals. He’ll be giving a talk and demonstration on the Electrosteel during the paper session before returning back to New Jersey to embark on the next step of the Electrosteel’s journey: building nine Electrosteels — possibly with the support of a few undergraduate students — to lend to nine carefully selected pedal steel players. “If I go to most countries in Europe or Asia or some places in South America, I can run into people who play the Manta. It’s been amazing for research purposes to see the instrument used in ways I didn’t expect and making music that isn’t the kind of music I make.” Snyder is hopeful that by lending the latest iteration of the Electrosteel to these musicians, he’ll garner important learnings for the instrument’s next — possibly final — iteration.

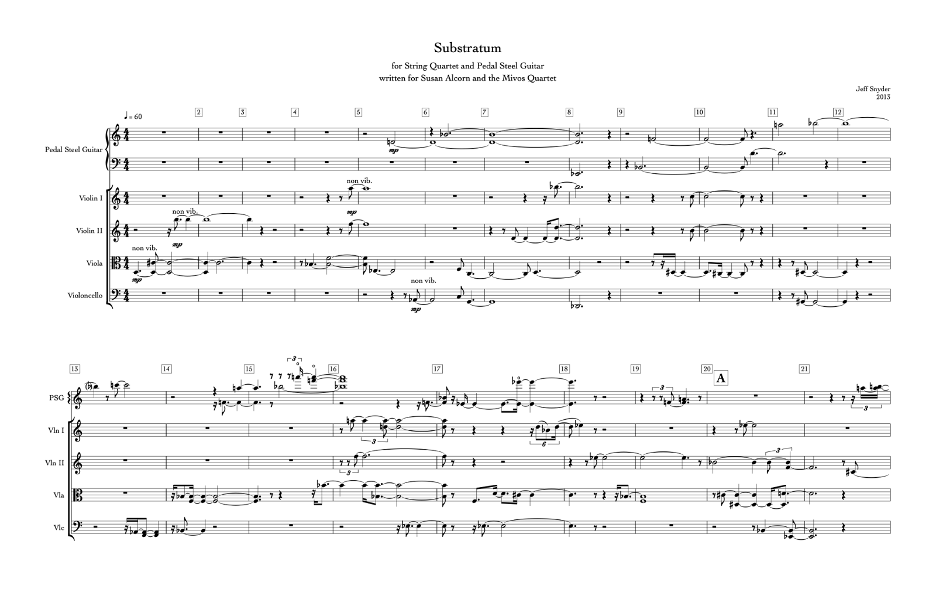

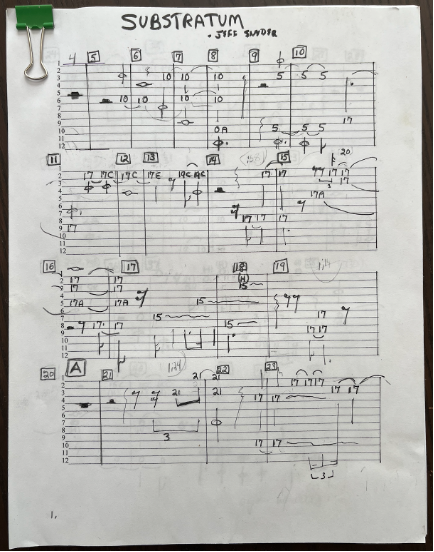

Snyder is also curious to see what sorts of notated musical scores come out of the experiment. When he wrote a piece for pedal steel guitar and string quartet back in 2013 for musician Susan Alcorn, he started writing it in tablature, an instrument-specific notation style that gives more specific details about how notes should be played on the instrument, until Alcorn requested that he use standard notation instead. Later, when Alcorn premiered the piece, she shared with Snyder the tablature version that she created from his standard notation score. Both were imperfect, unable to capture the entirety of the music, but they had their respective strengths. Notation remains a puzzle piece.

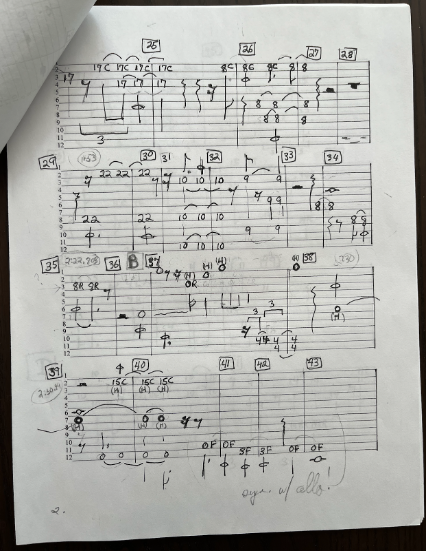

Standard notation of “Substratum”

“It is hard to notate for a pedal steel because there is so much detail that is missed.”

The Electrosteel is a manifestation of a curiosity that Snyder has held since grad school, but it’s also a vehicle that has enabled him to stay “keyed in” as an educator. He’s grateful to the many undergraduate students who have assisted him in the development of the instrument thus far and hopeful that they have found the process edifying and rewarding. Looking forward to the conference, Snyder is eager to bring key learnings back to campus for his upcoming work with students.

“I had a lot of input of other people’s ideas when I was regularly attending one or two conferences a year pre-COVID. That really helps with teaching — knowing what sort of sources to recommend to students and having a good sense of the field beyond my specialties.”

Preparing for the conference, Snyder has also made a recent update to the Electrosteel that will prove useful when he co-teaches MUS 545, a grad seminar on “idiosyncratic instruments,” with Dan Trueman in the fall: “Part of what I’m working on over the summer is playing around with a platform called Daisy, which is a hardware platform for microcontrollers that the composition grad students will be using in MUS 545. Daisy is actually really close to something I developed on my own, but the developers made it more approachable for beginners. Because I recently converted the Electrosteel boards from my own custom boards to Daisy boards, I’ve already identified a couple of snags that the students are going to hit; I’m trying to start from scratch on one of these boards the way a student would.”

“I’m trying to start from scratch on one of these boards the way a student would.”

In addition to his Electrosteel and MUS 545 preparations, Snyder will also devote his summer to mixing an album of electronic music that he recorded during his sabbatical year in 2020-21. “I was up in Maine, where my wife is from, and I set up a little studio in the barn behind the house she grew up in. I didn’t feel like making the heavy, contemplative music that I often make. I just wanted to make some grooves.” After abandoning his initial concept of dance music made exclusively with drums, he came up with something pretty exciting. “It’s influenced by the 1999-2000-era injection of experimentalism into dance music. But it also takes into account newer stylistic things that I’m interested in too.” That album will be released in the 2023-24 academic year on 577 Records, an experimental free-jazz label that has been branching out into electronic music.

Snyder is known for having numerous irons in the fire at all times, and this summer is no exception. We look forward to keeping up with both of his primary projects along with the inevitable tangents he will journey off on as the summer progresses. Thanks for sharing your summer plans, Jeff!

In Other News

Gavin Steingo Named 2024-25 Getty Research Institute Scholar

Jun 28, 2024

The Department of Music is excited to announce that Gavin Steingo, Professor of Music and Director of Undergraduate Studies, received a prestigious year-long fellowship at the Getty Research Institute (GRI) in …

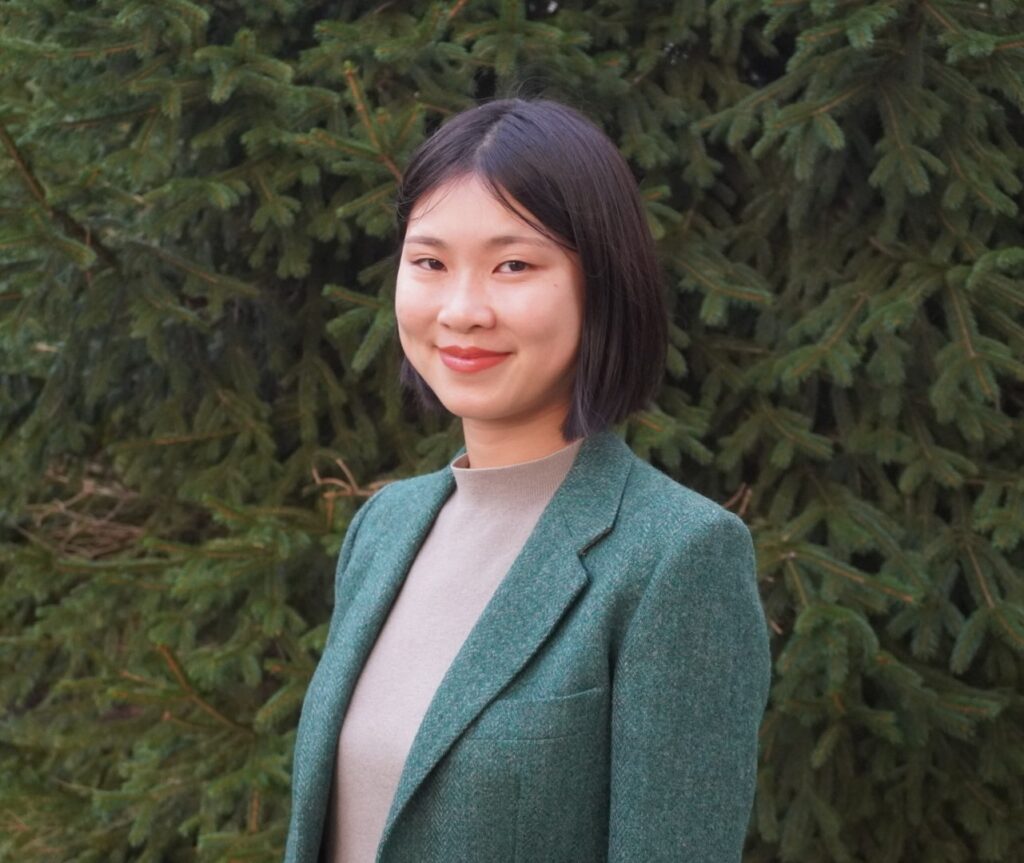

Anna Yu Wang Named 2024 Luce/ACLS Early Career Fellow in China Studies

May 24, 2024

The Music Department at Princeton is proud to announce that Anna Yu Wang has been awarded a 2024 Luce/ACLS Early Career Fellowship in China Studies.

Cultivating Aluminum Flowers: Inside Steven Mackey’s Latest Electric Guitar Concerto

May 6, 2024

Steven Mackey’s Aluminum Flowers, a concerto for solo electric guitar and orchestra, made its world premiere on March 9, 2024 at the Kimmel Center. This concert featured jaw-dropping virtuosity of polymath guitarist JIJI.